From filler in your labia to full labiaplasty, designer vaginasare a popular cosmetic surgery, with the procedure making it into the British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons (BAAPS) list of top procedures for women in 2023.

This is in spite of the fact that there’s no such thing as ‘normal’ when it comes to vulvas: one large-scale study found labias typically ranged from from 5mm to 10cm, and around 50% of women are believed to have asymmetrical labia.

Obstetrician and gynaecologist Dr Inês Vaz commented: ‘The concept of “big” and “small” was created by the media. Women should think twice before they categorise themselves as “abnormal”.’

And now, there’s a new part of the female anatomy receiving scrutiny: the pubic mound.

The pubic mound, or mons pubis, is the area of fatty tissue in front of your vulva, which lies over the pubic bone.

It’s perhaps more colloquially known as the ‘fupa’, an acronym that stands for ‘fat upper pubic area’.

Content creator Whitney Simmons posts workout and gym videos on TikTok, and her pubic mound is a source of unwanted attention.

‘One thing about me, y’all love to comment on it, I have a very prominent pubic bone okay,’ she says in one clip.

In another, she can be seen covering her pelvic area with her hands, saying: ‘My large oversized tee is dirty so today [my pelvic bone] is out, she’s large and she’s in charge.

‘I’ll just be like this all day,’ she adds as she demonstrated turning her back to the camera.

Whitney hasn’t had any cosmetic surgery, and her openness about the hate she gets has encouraged her followers to talk about their own anatomy.

‘I have a prominent one too. I call her my generous mons,’ commented Lydia (@depressy.monkey).

Alexis Lorentz added: ‘I am here to join the club for prominent pubic bones.’

Your body, your choice

A University of Melbourne study that found girls as young as 13 were already worried about how their vaginas look, but medical professionals stress that your natural anatomy is nothing to be ashamed of.

‘There is no “perfect” or “ideal” appearance for genitalia—just as with any other body part, every vagina is unique,’ gynaecologist Dr Shazia Malik previously told Metro. ‘Most concerns about vaginal appearance stem from societal pressures and misinformation, not actual issues.’

She warns that while discomfort or health concerns should be addressed with medical professionals, ‘cosmetic procedures should only be pursued if they are personally desired.’

‘It’s a personal choice, and like any cosmetic procedure, it should be approached with careful consideration,’ Dr Malik added.

‘While it can offer aesthetic benefits and boost confidence, it’s important you seek procedures for your own reasons and not because of societal pressures or unrealistic expectations.’

What is monsplasty?

Cosmetic surgery offers an antidote to this pubic mound insecurity, in a procedure called monsplasty.

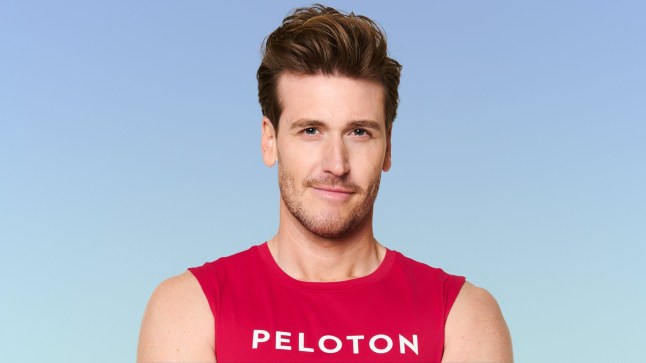

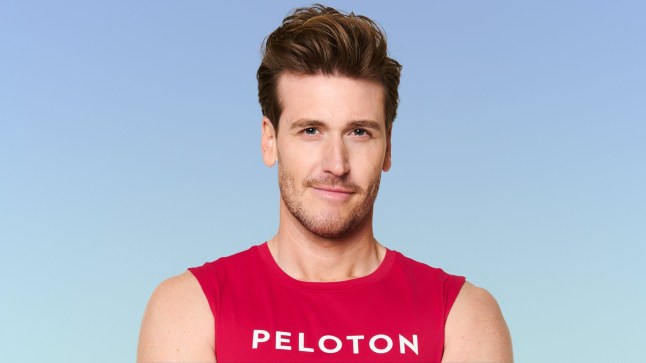

For plastic surgeon Dr Omar Tillo, medical director at CREO Clinic, there has been a growing interest in the surgery, which he believes comes from the influence of social media platforms showing different ‘body contouring’ options.

So what is it exactly?

Dr Tillo tells Metro: ‘Monsplasty, also known as a pubic lift or mons reduction, is a surgical procedure that addresses excess skin and fat in the mons pubis (the area above the pubic bone).

‘The goal is a smoother, flatter, and more contoured appearance, improving the balance and proportion of the lower abdomen and genital area.’

He explains that an incision is made along the bikini line, through which excess skin and fat are removed, and liposuction may be used to refine the contour.

‘The underlying tissues may be tightened, and the remaining skin is then carefully redraped and closed,’ he adds.

Dr Tillo says that he usually performs the procedure in tandem with abdominoplasty (a tummy tuck) but that it’s also done on it’s own. He performs on average 15 of the procedures a year.

What are the risks and benefits of monsplasty?

Dr Tillo claims that the women seeking the procedures are likely self-conscious about the area’s appearance, particularly when wearing fitted clothing or swimwear.

‘Some experience discomfort or chafing due to excess tissue, especially during physical activity,’ Dr Tillo adds. ‘Others may feel that the appearance of the mons pubis is disproportionate to their overall body image.’

As with any surgical procedure though, there are potential risks like infection, bleeding, scarring, asymmetry, changes in sensation and reactions to anaesthesia, according to the surgeon.

It’s also not cheap, with costs ranging from £2,400 to £4,000.

‘Making sure to choose a board-certified plastic surgeon with extensive experience in body contouring procedures is crucial to minimising these risks and ensuring the best possible outcome,’ he adds. ‘All these risks will be discussed in a consultation.’

Do you have a story to share?

Get in touch by emailing MetroLifestyleTeam@Metro.co.uk.